Join the ICONS

Dance ICONS is a global network for choreographers of all levels of experience, nationalities, and genres. We offer a cloud-based platform for knowledge exchange, collaboration, inspiration, and debate. Dance ICONS is based in Washington, D.C., and serves choreographers the world over.

Subscribe today to receive our news and updates. Become a member of your global artistic community -- join the ICONS!

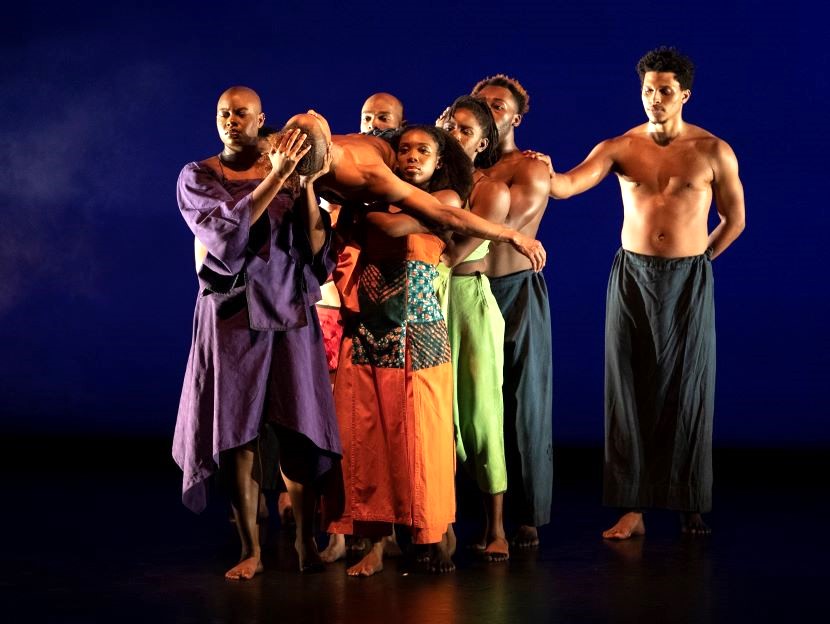

RONALD K. BROWN: EVIDENCE OF GRACE

American choreographer Ronald K. Brown has been at the forefront of dance in the US for the last four decades. Even after suffering a debilitating stroke in 2021, he continues to work in the studio, run Evidence/A Dance Company, and inspire the next generation of artists. Brown is known for his signature style, which effortlessly fuses dances from all over the African Diaspora with Western forms. He spoke to Dance ICONS, Inc. about his unique dance journey and the support system that enables him to continue working as a living legend in the field.

ICONS: What brought you into dance?

Ronald K. Brown: When I was eight years old, for my school trip in the second grade I went to see the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and then went home and made a dance. I started making up dances and making my family and friends watch these dances. Then my mom took me to Bedford-Stuyvesant Reservation Corporation, which is a community development center in Bed-Stuy and they had dance there. Just me and 80 girls, and so I fought with my mother for most of my life until I graduated school.

But it was that trip to Ailey that triggered it for me. My mother told me that even as a little boy in school, at the market, anytime I heard music, I was always dancing. And so, I decided to give up a journalism scholarship after high school, and my mother said, “I told you so, get a job and learn how to dance.” So it was a trip to see Ailey.

ICONS: You started Evidence/A Dance Company right after high school, which was an unusual path. Why do you choose to go right into directing and choreographing?

RKB: I was looking in the early 80s, and I was looking around at what was happening in the dance world. I really wasn't understanding the work. I mean, I understood why people were going in the direction of creating work. For me, though, the work was kind of absent of emotion because they were trying to develop a technique to find access into your body, absent of emotion. I was confused; I thought modern dance was supposed to be about people.

Then I talked to my colleagues about it, these big brothers in the industry. I said, “I don’t think that I want a dance company,” and they just challenged me. They said, “Who was going to tell your grandmother's stories?” So I felt that the responsibility was on me. If I didn't see the kind of work that I wanted to see that could feed me and people, it was my responsibility to put that work out. And that's actually why I call the company Evidence. So that when people come see the work, they see evidence of the human condition; they recognize their teachers, their families.

ICONS: Your dance vernacular expands beyond what dance in the late 20th and early 21st century was considered “for the stage.” You draw on every area of the African Diaspora. How did you become so familiar with all of the forms of this dance?

RBK: It’s a beautiful thing! I met a choreographer, Rokia Kone, who was from Côte d'Ivoire. We met at the American Dance Festival and she said, “You're doing something, you're making dance speak.” She was working with a theater company in Côte d'Ivoire founded by Solomon Coley, who was from Guinea.

They asked me to take dance from the village and make contemporary movement out of it. “Can you come to Côte d'Ivoire and teach contemporary dance to the theater company to help me?” And she wanted to start a dance company. So I started learning dances from Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea there so I could make sense of what I was going to create next. I think those were the first other cultures that I started to learn from. It really changed my life.

ICONS: But you also fuse these diasporic forms with Western classic forms to make a movement language that is recognizably you. How do you blend those two together?

RBK: In 2001, I went to Cuba for the first time, in a kind of a cultural exchange in Havana and then in Santiago, where we saw a lot of groups with a wide range. But then in Santiago, we learned Amritscha dances, dances from the Dalmais, so spiritual dances from the continents that came over to Cuba. And so for me, if I have an idea for a piece, you know, there's all this material, the Western styles, and the African brief styles are my resources. I just improvise and go from one to the next. It seems that there's something that makes sense to tell a story. I don’t think about them as separate. They all are storytelling tools, so I go from one to the another.

ICONS: Grace, your first work for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, was a huge breakthrough for you as a choreographer, and a signature in your company's repertory. Grace celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. How did you create it, and did you realize its significance at the time?

RBK: I had no idea. I was grateful when Ms. Jamison asked me to create something for the company. And that's how the name Grace came right away, because I was a little boy who didn’t want to take dance classes, but was inspired by Mr. Ailey in the first place.

I was like, “How did I get this chance? It was Grace.” That’s how I came up with the title. At Ailey, I was given three weeks to create a piece. I started on Monday, but by Wednesday, they wanted two casts, right?

I prefer to choreograph in the studio with dancers. But for this situation, I knew I had to audition dancers to cast. I built most of it on my company, Evidence. I walked in there with a lot of material since I didn't have much that first time around. It changed after the fifth time I was working with the company. I had no idea that it was going to be what it was, what it is, and definitely not that it would still be as relevant as it is 25 years later.

ICONS: You're also now the co-artistic director of Bed-Stuy Restoration, the community center that you mentioned earlier where you took your first dance class, and Evidence is a huge part of the center now, right?

RBK: Evidence has been rehearsed here for over 20 years. And Arcell [Cabuag] and I are co-directors of the pre-professional training program. But Arcell is the Director of Education for the whole school: drama, drumming, and dance, just to mention a few. It's incredible to be here at Restoration and from that first dance class. Education is a large part of what Evidence does.

I get to meet amazing people of all ages and give them access to express themselves. It’s so rewarding to see them blossom. Eventually it comes around if it's right. There's a woman we just hired who used to take my community class with her mom when she was a child. And now she graduated from college, she auditioned with 180 other people, and we selected her. But then last week she took class with her mom again. How amazing is that?

ICONS: What's the hardest part of being a choreographer for you?

RKB: It’s always having to raise money. I really want to create the work. Then part of me always has to be focused on, can we make payroll? We need how much more money? That's the challenge.

ICONS: A few years ago, you suffered an awful stroke, but you're teaching, choreographing, setting work, running around the world again. How did that scare impact your choreographic process and your view of your works?

RKB: God bless Arcell Cabuag and the doctors who got me to stand up and walk. The first day we were about to come to rehearsal, I was kind of panicking while waiting for the car to pick us up. Like, what am I going to do in this rehearsal? I got to rehearsal. I just directed as I always would, right back into giving notes. It's been incredible to really continue to work. It's great to be able to work with the repertoire that we have already and just give our new dancers more of an understanding of the work.

ICONS: Is there anything that you would tell your younger self when you were starting out Evidence, any advice or insight you would give yourself?

RKB: Take care of yourself so you don't get too exhausted and get the help that you need right away. When Arcell joined, I was writing grants and booking flights and all that stuff. He said, “Can I help out? Can I take this off your plate?” And it was amazing for someone to take this load off. I wish I had known to ask for help sooner. But it's been divine, and he's been my lifesaver ever since.

* * * * * * *

PHOTO CREDITS:

© Quinn Wharton, photo portrait of Ronal K. Brown

© Steven Pisano, Paul Kolnik, Rose Eichenbaum, Julieta Cervantes, photos of dancers of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and Evidence /A Dance Company

© Media materials and photos provided by Evidence/A Dance Company

© Newsletter template video banner photo credit: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater's Ashley Kaylynn Green and Patrick Coker in Ronald K. Brown's Grace. Photo by Nir Arieli

BIOGRAPHY OF RONALD K. BROWN: https://evidencedance.com/mission-founder/

VIDEO SAMPLE OF ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER: GRACE, CHOREOGRAPHY BY RONALD K. BROWN:

INTERVIEW'S CREATIVE TEAM ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

Interviewer: Charles Scheland

Executive Content Editor: Camilla Acquista

Executive Assistant: Charles Scheland

Founding and Executive Director: Vladimir Angelov

Dance ICONS, Inc., September 2025 © All rights reserved

This digital resource and publication was made possible with funding from

![]()