Join the ICONS

Dance ICONS is a global network for choreographers of all levels of experience, nationalities, and genres. We offer a cloud-based platform for knowledge exchange, collaboration, inspiration, and debate. Dance ICONS is based in Washington, D.C., and serves choreographers the world over.

Subscribe today to receive our news and updates. Become a member of your global artistic community -- join the ICONS!

AKRAM KHAN: DANCING CREATURE

Akram Khan’s distinctive blend of Kathak and contemporary dance is the hallmark of his award-winning choreography. A Londoner of Bangladeshi heritage, he brings to the arts the voice of the outsider with unique creations related to the twenty-first century. His timing is serendipitous, as ballet cautiously welcomes diversity. He spoke with Maggie Foyer of ICONS about his upcoming fill-lenght work, Creature, of the English National Ballet, which premieres now in September, 2021.

ICONS: When did you first encounter dance?

Akram Khan: I started learning dance at three with my mother and my auntie. Then I went to Classical Indian Dance classes and that was like joining the Royal Ballet. I was quite a shy kid. Language is not my first form of communication – my body is. My mother said I could just about say a sentence in English at seven, but when I was four, I could memorize a ten-minute choreography. My language was always movement.

ICONS: So there was no parental opposition to dance?

AK: No, but there was opposition to it in my community, which was conservative and highly academically driven. All my mates became doctors, lawyers, accountants, and engineers. None of them went into the arts. But my mother really believed in me, and my father to a certain extent. She pushed me to get a degree and said I could do what I wanted after that, but I had to get the degree. She felt education was important and she was right.

ICONS: You studied dance at De Montfort University in Leicester?

AK: Yes, and then at Northern School of Contemporary Dance. Northern was about technical training, tuning the body, and preparing the dancer of the future. De Montfort gave me the freedom of the mind - and the mind is also a muscle. It was a great insight.

ICONS: So, was it when you came into contact with contemporary dance that the possibility of choreographing opened up?

AK: Absolutely. De Montfort opened my mind to Judson Church and Steve Paxton. I read about them and studied their work on videos.

ICONS: Did you consciously feel you were building a choreographic identity?

AK: I was just searching; I was not so conscious of it until I met Farouk Choudry (my executive producer) and formed the company in 2000. With my company, I had the space to explore without judgment and find an aesthetic and a movement language. The aesthetic was subconscious and matured later, but the language was already maturing quite quickly because predominantly it started with my body. Very creative people like Moya Michael, Shanell Winlock, and Inn Pang Ooi joined and the language quickly started to transform and be more versatile. The aesthetic started to take shape more when I did Zero Degrees, the duet with Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui.

ICONS: In Kathak dance is there the possibility for improvisation?

AK: Yes, there is in terms of rhythmical improvisation and more so than the other Indian classical dance forms. In terms of narrative storytelling, it does have improvisation, but Bharathanatyam has more. In Kathak it’s the musical rhythms they improvise. The dancer is the musician as well as the actor; in Indian arts, we don’t separate the actor from the dancer. The dancer has to be all three. That is something Peter Brook believed in too. In a sense, there wasn’t really a development of movement improvisation, but in storytelling improvisation, yes!

ICONS: What was the influence of Peter Brook in shaping you as a choreographer?

AK: I was in the world tour of Peter Brook’s Mahabharata, the nine-hour theatre epic. It was a roller coaster and it shaped my entire way of seeing the world and the way I relate to the world through art. I was 13 when I joined and 15 when I left, and I owe a lot to my mother for letting me go. It was from working with Peter Brook and being surrounded by great actors from many countries that I learned how to be an artist and how artists relate to art. It was about storytelling and that was really important. I learned the rigor of training, the rigor of rehearsing, the rigor of practice, and how the performance is always evolving.

ICONS: In 2012 you used your Bangladeshi heritage in creating your solo, DESH. You have now made a children’s version, Chotto Desh, and now with Xenos, a much darker work about an Indian dancer returning from the First World War. What was your thinking behind this?

AK: DESH was already quite child-friendly. It was about my childhood, so it offered itself to me. I remember trying to be like Michael Jackson, and every teenager knows how it is with parents trying to teach you about their stories, their history, and you not wanting to listen. The material is very relatable. For Chotto Desh, I invited Sue Buckmaster to direct it because it’s important for young people to understand another perspective of history, that there are people from other cultures that are similar. They are not ‘Xenos’ (foreigners) as society or government wants us to think they are.

That is one of the biggest problems: Who writes history? We are told myths from when we are a baby. Why does a boy think he is stronger than a girl? And what is a strength as well? Is it only physical strength? But in the posters, the cartoons, the programmes, everything is already constructed in that way. Men are the strong ones and women are the submissive. It’s so wrong, right from the beginning the myths are wrong because most of the myths are written by men! But I think there is a real shift happen.

ICONS: You are working on your next piece with English National Ballet, Creature. What are the themes and what was the inspiration for this work?

ICONS: You are working on your next piece with English National Ballet, Creature. What are the themes and what was the inspiration for this work?

AK: The theme has shifted from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and is now more Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck. Actually, I would say it’s entirely Woyzeck. We’re leaving some ambiguity, but it’s a human being that has become a creature – the animal within us. He has been turned into a creature by society’s behavior towards him. He represents, in a sense, how society is breaking down that very thin line between being civilized and not being civilized. Because we are under pressure, it is being broken so quickly. At the moment, we are not subtle in the way we treat “the other,” the ones who are not like us, whether it’s Brexit or a homeless person.

ICONS: In Woyzeck, the man is dehumanized by the military and the doctors. Were you thinking of a specific group when you started your research?

AK: Yes, the politicians. I created the character of the Major to represent the powerful who have complete control over our lives. Even more than the politicians, it’s the ones with the money. The politicians have become puppets and the middle class has gone in terms of power. It’s now about the rich and the poor. Art has to speak for what we believe in. It has never been separate from politics. So, using the situation we’re experiencing in the world today, how do we heighten that into art?

ICONS: Where does the creative process start?

AK: With my creative collaborators, and we spend a year working with the idea before we get into the studio. That will be Ruth Little, my dramaturg; Michael Hulls, lighting designer; Tim Yip, visual and costume design; Vincenzo Lamagna, my composer; Mavin Khoo, my rehearsal director; and Andrej Petrovic, who is assistant choreographer. So, we are all in the room for a year - not continuously - but coming back to it and workshopping ideas. This is the cerebral phase of what we want to tackle, but once you’re in the studio, that’s a very separate process.

ICONS: Before you start to work on the movement, do you have the structure of the set, the music, and the lights? When do all the elements come together?

ICONS: Before you start to work on the movement, do you have the structure of the set, the music, and the lights? When do all the elements come together?

AK: At this stage, it’s more of an engagement than a complete commitment. The absolute committing phase, when you marry all the design elements, is much further on in the process. Conceptually, there is a theoretical process; then there is a practical, physical process, and once we’re on stage, the set will encourage us, even force us, to make changes. So the lighting design that Michael might have in his head might not feel right with the scene. But there are some firm ideas; for example, the set was decided a year ago. Because it’s such a tight timeline with so many people involved, we have to commit to the theoretical idea early on.

ICONS: When do you start on the choreography?

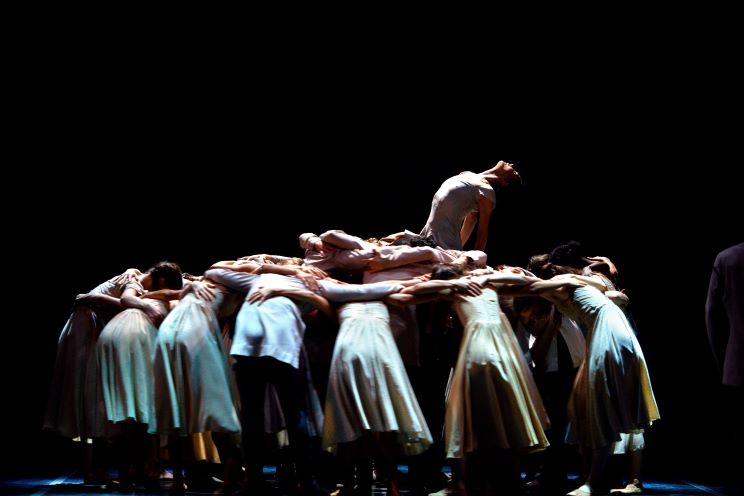

AK: The movement ideas start pretty early. I think in movement, and I’m moved by narrative, so there is always motivation behind the movement. I used to work in a more abstract way, but in this work, it’s never just about the look or the pattern. Of course, there is structural complexity and physical patterns but not just patterns that are impressive; they have to carry the narrative forward. When they stop doing that, we are very conscious of how long we can rest with it and not take it forward, and then we decide on a cut-off point. The dynamic and energy of the pulsating mass is a physical metaphor to hold the narrative for a time.

ICONS: What role do the dancers play in creating the choreography?

AK: I worked with a group of research dancers three weeks before rehearsal started, and Jeffrey [Cirio], who plays the lead character, was in right from the beginning. His opening solo formed the foundation, the basis of his character. The research dancers are not all from English National Ballet - there were only about three or four from the company. I also had a dancer from Nederlands Dans Theater, but it was very important that they were all classically trained. The work is not for my company. It’s for a classical dance company, so it was important the research dancers could reflect the classical bodies, that they have that classical knowledge. I developed a great deal of material with the research dancers and they contributed a lot, especially Jeffrey; he’s such a force of nature, so intelligent.

ICONS: The dancers in rehearsal are performing movement vocabulary very different from their usual classical ballet repertoire. Was the process like?

AK: It’s about choosing intelligently between what [movement] material looks good when they go to the threshold and what material doesn’t look good. Transforming dancers’ movement doesn’t happen overnight; it’s years of work. In my company, our direction is towards the floor, and in ballet companies, it’s away from the floor.

ICONS: Is the shift as extreme as when you created your Giselle for the company in 2016?

AK: Giselle lent itself to this company because 70-80% was taken from their language and then I transformed it. Only 20% was mine, taken from my world. With Creature, 70-80% is from my world and 20% from theirs. So it’s a tremendous shift. And there are no pointe shoes. Pointe shoes were right for Giselle - they became like daggers. And Giselle was the first time the ballet world committed to dancing on pointe because of the Wilis, so it lent itself.

ICONS: Setting aside the movement qualities, what are the pluses and minuses between working with your own company and with English National Ballet?

ICONS: Setting aside the movement qualities, what are the pluses and minuses between working with your own company and with English National Ballet?

AK: Well, the pluses in my company are the minuses in this company and vice versa here. It’s not about having more or less freedom; it’s about a different kind of freedom. I think the difference is mass. This is a much larger group, and the effect I can create with 30 dancers, I can’t necessarily create with six dancers. So that’s a plus point. It’s extraordinary to have such a number of dancers, and the other plus point is they all speak the same language. In my company, the dancers come from different traditions and from very different backgrounds in their training. Some are from Indian classical dance, some are from breakdance, some are from neoclassical dance and some are from purely contemporary dance. It’s a collective of distinct and very different training, different vocabulary, and language. In my company it’s about bringing the commonality, finding the common denominator, whereas here, it is already in place. So, it’s about going the other way and finding the individual vocabulary that separates some dancers from the others.

ICONS: In Creature/Woyzeck, what role does the ensemble play? Are they the socially conditioned society trained up as a military force?

AK: Yes, and really what the work is based on is where we are in the world today. It’s what Elon Musk is talking about that we should give up on earth and move to Mars. Setting up a human colony on Mars is the first step. However, its harsh climate makes it impossible for human habitation. Creature is based on that project. We have taken Woyzeck as a structure, but we’re not basing it exactly on the play in the same way as my Giselle was not based on the original story in a European village and royalty, but on what we are experiencing today. Creature is also based on the now and the future. There is research going on now testing people in laboratories and communities to see if they can survive in very harsh conditions. The temperature on Mars reaches minus 60, plus there is a lot of radiation.

It’s about the survival of the richest and the most powerful. The creature here is being tested to see if he can survive outside this hut with the suit and the helmet on. He’s the guinea pig. When he is given the go-ahead by the doctor saying he can survive, that will mean that we are going to survive in this suit. At that point, they leave him.

ICONS: So, it’s about abandonment?

ICONS: So, it’s about abandonment?

AK: Yes, and it’s similar in a way to the monster in Shelley’s Frankenstein. The monster felt abandoned by his master and, in a sense, this creature feels abandoned. He wants a connection. He needs a sense of belonging. He just wants love.

ICONS: And Marie, Woyzeck’s common-law wife? Does the Creature get any affection from her?

AK: Yes, he does, but in my version, Marie chooses to leave with the Major. She wants to live and nobody is going to survive on this earth destroyed by climate change. The Major has a different role and a different agenda.

ICONS: You have painted an extremely desolate scene.

AK: I don’t mind it being desolate. What I’m really sad about is that it’s not a Hollywood story. I mind that it’s not fiction. Ruth and I, the team, based this work on everything we’ve found through our research. It’s what scientists and the army are researching right now, right under our noses. We’re distracted by the politics, the xenophobic stuff, but underneath there is work being done to leave Earth. We are controlled by very few people and we don’t even know who they are. We are all expendable right now - we always have been, but it’s not been necessary to enforce it because there were sufficient resources. When resources run out, then people are expendable. It’s the beginning of the end for us. The earth will never be the same; we’ve raped it too much. We’ve not treated Earth-like the ancient cultures used to treat it. They were part of nature, and for them nature was God. Now we have placed ourselves as God and we’ve used nature to our advantage. We think we control Earth, but we do not.

ICONS: What about the Major – is he evil or is he, like Woyzeck, conditioned by social circumstances?

ICONS: What about the Major – is he evil or is he, like Woyzeck, conditioned by social circumstances?

AK: It’s more complex than that. What I’ve discovered and what I’m trying to share is that in all the characters, even the good characters, there is bad. I can’t just say Trump is bad. We’re all part of climate change. We all contribute to CO2 - we all drive cars, we fly, we all waste food, so we’re all part of it. We are all interconnected and it’s not as simple as one is good and one is evil. Good versus evil has always been a Western tradition. Whereas an Eastern approach to narrative is, especially in Hindu mythology, so much more complex because within the good, there is bad. When you make a good choice, it is simultaneously a bad choice for somebody else. So, it’s not easy. It’s the fundamental human condition. The complexity of the human condition is never just right or wrong. It’s not Facebook, where you have two gestures that define your way of treating someone: like and dislike. Just those two! Human relationship is so much more complex than that. You may like someone, but you may often not like parts of them. You might love somebody, but you may also hate parts of them. But technology has flattened that relationship in society and we’re evolving by the force of technology.

When people say art is not political, that is a political statement. It is choosing not to relate to the politics of the world, but that is a political statement. Speaking to power, good or bad, is just as much action as being silent. Being silent is a political action.

ICONS: In all the diversity in your work, is there a common thread?

AK: I think it would be - what is the human? I’m constantly trying to use stories to navigate and research what it means to be human.

Creature, a new ballet production by Akram Khan and his second full-length work for English National Ballet, opens September 23, 2021, and runs through October 3, 2021.

Promo Video Link:

More About Akram Khan and his biography can be found at:

https://www.akramkhancompany.net/company-profiles/akram-khan/

Photography Credits:

1. Photo © Lisa Stonehouse. Akram Khan portrait, 2016

2. Photo © Jean Louis Fernandez. Pictured Akram Khan in XENOS, 2017

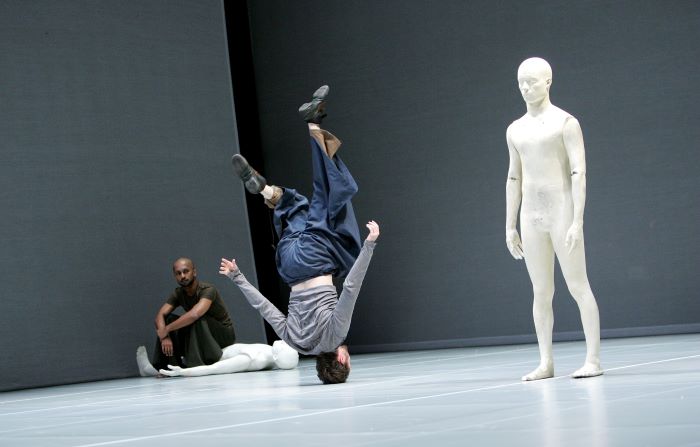

3. Photo © Tristan Kenton. Pictured Akram Khan and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui in Zero Degrees, Sadlers Wells, 2005

4. Photo © Laurent Liotardo. Giselle, choreography by Akram Khan, pictured James Streeter, 2019

5. Photo © Laurent Liotardo. Giselle, choreography by Akram Khan, pictured Stina Quagebeur and Jeffrey Cirio, 2019

6. Photo © Laurent Liotardo. Giselle, choreography by Akram Khan, pictured Tamara Rojo, 2019

7. Photo © Laurent Liotardo. Giselle, choreography by Akram Khan, pictured Stina Quagebeur, Tamara Rojo, and James Streeter, 2019

8. Photo © Laurent Liotardo. Giselle, choreography by Akram Khan, pictured Tamara Rojo, 2019

Photography Credits for Newsletter Template:

1. Photo © Lisa Stonehouse. Portrait Akram Khan, 2016

2. Photo © JP Maurin. Pictured Akram Khan and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui in Zero Degrees, Sadlers Wells, 2005

3. Photo © Carl Fox. Pictured Akram Khan in Zero Degrees, Sadlers Wells, 2005

Interviewer: Maggie Foyer

Content Editor-in-Chief: Camilla Acquista

Dance ICONS, Inc., September 2021 © All rights reserved.

![]()